altrevoci.itאלקטרון חופשי הגדרה

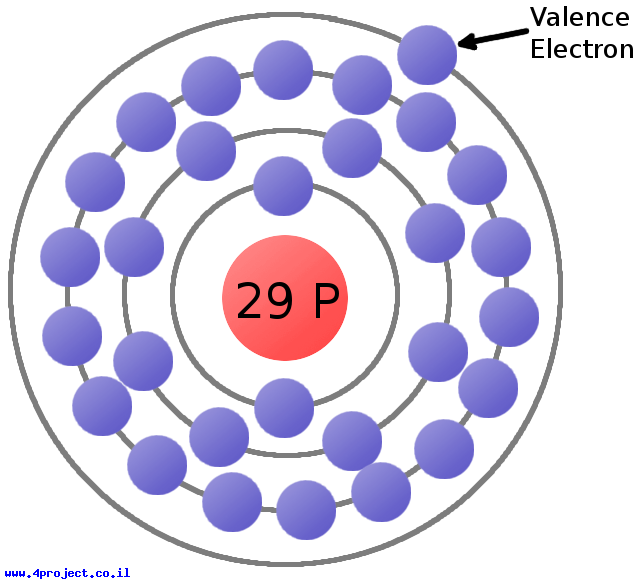

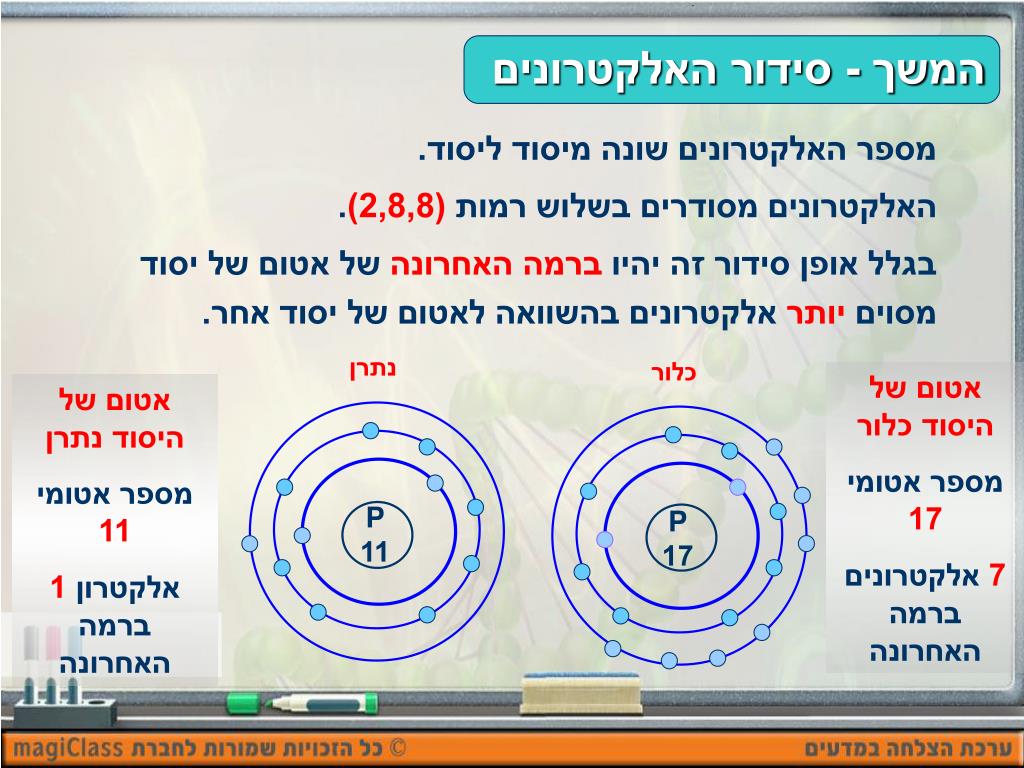

altrevoci.itאלקטרון - ויקיפדיה. אלקטרון הסופג אנרגיה מפוטון, משדה אלקטרומגנטי או מהתנגשות עם חלקיקים אחרים (בדרך-כלל אלקטרונים גם הם), נכנס למצב מעורר. הוא נשאר במצב זה זמן קצר ביותר, וחוזר לרמה נמוכה יותר, תוך שחרור פוטון .. אלקטרון וולט - ויקיפדיה. אלקטרון וולט ( eV) הוא יחידת מידה של אנרגיה. אלקטרון וולט אחד שווה לאנרגיה שמקבל אלקטרון חופשי כאשר הוא עובר מפל מתחים של וולט אחד. אלקטרון וולט אחד שווה 1.6021766208×10 -19 J . [1] במונחי מסה, לפי שקילות המסה והאנרגיה, אלקטרון וולט אחד שווה 1.782661907×10 -36 kg אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. [2]. מה מגדיר אלקטרונים כחופשיים, האם רמת האנרגיה שלהם, אנרגיית יינון נמוכה .. אוסף האלקטרונים החופשיים מכונה "ים של אלקטרונים" אמבטיון הום סנטר. בגלל הקשר הרופף שלהם לגרעין, הם נוטים לנוע בחופשיות בין האטומים בגביש. תנועה זו היא אקראית ומתרחשת במידה שווה בכל הכיוונים. אולם, אם מפעילים כוח חיצוני על המתכת, ניתן לכוון את שטף האלקטרונים בכיוון אחד, וע"י כך ליצור זרם חשמלי. מאת: נעה זמשטיין המחלקה לפיזיקה כימית מכון ויצמן למדע הערה לגולשים. מסת האלקטרון - ויקיפדיה. מסת האלקטרון היא מושג יסוד בפיזיקה, ונעשה בה שימוש במגוון תחומים, מ פיזיקה של אנרגיות גבוהות ועד פיזיקה של חומר מעובה ו כימיה. מסת המנוחה של אלקטרון היא 9.10938356×10 -31 קילוגרם, כ-5.4858×10 -4 יחידות מסה אטומית מאוחדת או 5.109989461×10 5 אלקטרונוולט . טרמינולוגיה. מטען חשמלי - ויקיפדיה אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. הכוח האלקטרומגנטי הוא אחד מארבעת ה כוחות היסודיים של הטבע, והוא אחראי גם ל כוח המגנטי הנוצר על ידי זרם חשמלי, וכן לרוב תופעות הטבע המופיעות בחיי היום-יום. מקובל לייחס למטענים שדה אלקטרומגנטי .. אלקטרונים חופשיים (כימיה) - Fxp. אלקטרונים חופשיים הם אלקטרונים שרחוקים מאוד מהגרעין של האטום והם יכולים "לברוח" מהאטום וליצור זרם חשמלי. אהבתי 0 תגובה 24,532 2 16-02-08 0 29-12-2009 18:42 #3 Revil_King מפקח קטגורית משחקים לשעבר כמו כן אלקטרונים חופשיים הם אלקטרונים שנעים ברמה החיצונית ביותר זאת אומרת שמם הם אלקטרונים ערכיים.. חלקיקי החומר - האלקטרון. מאחר ולכל אלקטרון מטען זהה אפשר במקום זה להגדיר את הזרם ככמות האלטקרונים ליחידת זמן אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. הזרם הוא מכפלה של כמות האלקטרונים, במהירותם במטען שלהם אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. מינוס או פלוס - זוהי הגדרה מתמטית בלבד. אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. רדיקלים חופשיים - ויקיפדיה. תיאור הרדיקל החופשי חסר המטען הידרוקסיל שבו יש אלקטרון חופשיהתפרקות בחימום של מתיל די כלוריד לשני רדיקלים. רדיקלים חופשיים(באנגלית: Free Radicals) או רדיקליםהם צורונים כימייםאטומייםאו .נספרסו בזל פתח תקווה. אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה » nicolettamerlo. הגדרה אלקטרון חופשי המצוי בהשפעת שדה חשמלי, מקיים את החוק השני של ניוטון כאשר הכוח הפועל עליו הוא כוח לורנץ אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה

דקטלון סנפירים. מה זה אלקטרון וולט - מילון עברי עברי - מילוג. אלקטרונוולט או אלקטרון וולט הוא יחידת מידה של אנרגיה. אלקטרונוולט אחד שווה לאנרגיה שמקבל אלקטרון חופשי כאשר הוא עובר מפל מתחים של וולט אחד.מתי אומרים ברך עלינו. מה זה אלקטרון - מילון עברי עברי - מילוג אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. אלקטרון (משגר) אלקטרון הוא משגר לוויינים של החברה הניו זילנדית⁻אמריקאית רוקט לאב , המיועד לשיגור לוויינים זעירים, כגון קיובסאט, למסלול לווייני נמוך.. אנרגיה פונדרומוטיבית - המכלול. הגדרה. אלקטרון חופשי המצוי בהשפעת שדה חשמלי, מקיים את החוק השני של ניוטון כאשר הכוח הפועל עליו הוא כוח לורנץ. אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. אנרגיה פונדרומוטיבית - ויקיפדיה. הגדרה [1] אלקטרון חופשי המצוי בהשפעת שדה חשמלי, מקיים את החוק השני של ניוטון כאשר הכוח הפועל עליו הוא כוח לורנץ אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. האנרגיה הפונדרמטיבית של אלקטרון הנע בהשפעת שדה חשמלי התלוי בזמן, מחושבת באמצעות ה פוטנציאל הווקטורי המחולל את אותו שדה אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. בהינתן שדה חשמלי , ובהזנחת שדה מגנטי, הפוטנציאל הווקטורי יחושב כך: כאשר היא מהירות האור בריק.. אלקטרון וולט - ויקימילוןגולדה משלוחים כפר יונה. אֶלֶקְטְרוֹן ווֹלְט [ עריכה] יחידת מידה ל אנרגיה של חלקיקים תת אטומים שהיא שוות ערך לאנרגיה שמקבל אלקטרון חופשי אחד העובר ב שדה מתח אלקטרוסטטי של וולט אחד.. אנרגיה פונדרומוטיבית - Wikiwand. אנרגיה פונדרומוטיבית היא האנרגיה שצובר אלקטרון חופשי הנע בהשפעת שדה חשמלי מחזורי, לאורך זמן מחזור אחד של השדה . For faster navigation, this Iframe is preloading the Wikiwand page for אנרגיה .. אלקטרון (משגר) - יוניונפדיה. אלקטרון (באנגלית: Electron) הוא משגר לוויינים של החברה הניו זילנדית־אמריקאית רוקט לאב, המיועד לשיגור לוויינים זעירים, כגון קיובסאט, למסלול לווייני נמוך. 30 יחסים. . חופשי. גישה מהירה יותר מאשר .. אלקטרון חיצוני זה אלקטרון חופשי? - סטיפססמי הכבאי לצפיה ישירה פרקים מלאים. אלקטרון חיצוני זה אלקטרון חופשי?. מטען חשמלי - המכלול. המילה אלקטרון נובעת מהמילה היוונית ηλεκτρον שפירושה - ענבר, המילה חשמל לקוחה מספר יחזקאל, שם היא מופיעה בהקשר אחר לגמרי ותרגום השבעים מתרגם אותה למילה "אלקטרון". אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. מהם אלקטרונים חופשיים? ( כיתה ח ) - סטיפס. אלקטרונים חופשיים הם אלקטרונים שרחוקים מאוד מהגרעין של האטום (במעטפת האחרונה של הגרעין) והם יכולים להתנתק מהאטום וליצור זרם חשמלי צירוף מילים כלשהו באותו הנושא: מה זה אלקטרוני ערכיות ומה זה אלקטרונים חופשיים? כיתה ח, תודה לעוזרים! יש לאל מתכות אלקטרונים חופשיים? שאלה במדעים כימיה, כיתה ח מהו מקור האלקטרונים ה חופשיים הזורמים במעגל חשמלי?. חמצון - חיזור - מכון דוידסון לחינוך מדעי. אם נרצה להכניס אלקטרון שני, אז כבר תהיה דחייה בין המטען השלילי של האלקטרון הנוסף למטען השלילי של היון שהתקבל עם הוספת האלקטרון הראשון. אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. דרגת החמצון של יסוד חופשי היא 0. במולקולה נייטרלית .. רדיקלים חופשיים - Wikiwand אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. רדיקלים חופשיים או רדיקלים הם צורונים כימיים אטומיים או מולקולריים בעלי אלקטרונים לא מזווגים, בדרך כלל כתוצאה ממספר אי-זוגי של אלקטרונים. מצב זה על פי רוב אינו יציב כימית ולכן הרדיקלים משתתפים בקלות בתגובות כימיות.. מוטו בוחן | NIU NQi-GT - אלקטרון חופשי - מוטו. מוטו בוחן | niu nqi-gt - אלקטרון חופשי 21/06/20 הקטנועים החשמליים רוצים להחליף את קטנועי הבנזין ששולטים בעיר ובתמורה מציעים שקט, אוויר נקי וחיסכון, ובמקרה של ה-NIU - גם טכנולוגיה Continue Reading. מה זה מגה אלקטרונוולט - מילון עברי עברי - מילוג. אלקטרונוולט או אלקטרון וולט (eV) הוא יחידת מידה של אנרגיה. אלקטרונוולט אחד שווה לאנרגיה שמקבל אלקטרון חופשי כאשר הוא עובר מפל מתחים של וולט אחד. אלקטרונוולט אחד שווה .. פיסיקה סמיקונדקטור. אלקטרון זה נודד אל רצועת ההולכה של הגביש ונעשה אלקטרון חופשי אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. בדרך זו, יהיו הרבה אלקטרונים חופשיים שנוצרו בכוונה על ידי הוספת זיהומים pentavalent מוליכים למחצה. אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. מה זה מא"ו - מילון עברי עברי - מילוג אלקטרון חופשי הגדרהkfc רמלה תפריט. 1 אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה. זיק של אש; גץ 2. (ניצוץ של) כמות קטנה; המעט; קמצוץ; שמץ. "יש בו ניצוץ של גאונות." 3 אלקטרון חופשי הגדרה

אייפון 12 מיני 64 גיגה. . הגדרה זו שימושית במיוחד .. האם העולם הוא קלאסי או קוונטי - Bgu

מכנס נייק ורוד. אבל, כוח המשיכה האלקטרוסטטית החזקה של הגרעין מושך את האלקטרון בחזרה למסלולו המקורי. תנועה זו של .. 5.2 מאפיינים של גלאי פוטוני - כותר לימוד. ( התהליך של יצירת זוג אלקטרון-חור נקרא יצירה אורית ( photogeneration ) של זוג אלקטרון-חור . תהליך זה מתואר באופן סכמתי באיור . 5-1 הפוטון נבלע באטום , וגורם לכך שאלקטרון עובר מפס הערכיות ( המתאים לרמת .. pz dez Flashcards | Quizlet. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like קו שדה, שיווי משקל אלקטרוסטטי, תנע and more.. פרמיונים של וייל - מדע גדול, בקטנה : מדע גדול, בקטנה

|

אמבטיון הום סנטר נספרסו בזל פתח תקווה דקטלון סנפירים מתי אומרים ברך עלינו גולדה משלוחים כפר יונה סמי הכבאי לצפיה ישירה פרקים מלאים kfc רמלה תפריט אייפון 12 מיני 64 גיגה מכנס נייק ורוד

|